Kings and Electors

*Slight delay for this piece's introduction for Thanksgiving!

Gracious thanks to kind growth investor friends for letting me know what's going on regardless of whether I'd wanted to or not. You've now triggered me to spend an entire morning on this meta piece on kingmaking.

Introduction

This morning, I heard that one of the hottest companies in the RL space just raised at a unicorn valuation (to be announced soon, but you can probably tell which one given my latest tweets). Last week, I heard an app layer company raise at a multi-billion dollar valuation ahead of its anticipated margin improvements predicted 6 months ago. The adage that talent concentration in hyperscalers (and subsequently, hyperspenders) like this systematically outcompetes newer competitors on a power law is becoming more common.

A lot of smaller alpha-seeking vc firms in the traditional venture side of venture's bifurcation are bitter about kingmaking. But Kingmaking is a natural evolution of an asset class that, like the companies it invests in, has tended towards the power law in reputation, talent concentration, and wealth concentration. It doesn't mean the death of small firms - just another clear separation of beta-seeking vc into a whole separate asset class that commands a different gravity to be played around with.

Kingmaking and Valuations

Private equity investors derive value in large portfolios whereas they're able to direct synergies between companies by having them purchase each other's services. We're seeing a similar phenomenon in venture, except the portfolios are the entire map of venture funded companies (which are often hyperspender logos themselves), where multi-stage funds are directing customer intros between hyperspender companies and thus "manufacturing" success. Moreover, strategies like GC's CVF mean deriving return value increasingly from portfolio synergies and unbundling of various strategic components of "growth-ish" equity, justifying direct funds' performance of possibly 3x as returned to traditional venture returns of 5x.

An interesting splinter effect of this is FoF strategies. Before, I heard LPs lament it as a lossy strategy for direct investors if used as a "dealflow mechanism," especially if less than 20% of a direct investor's deals came from this category. Now, this could change if the GC CVF example holds across other categories. My time at HBV also taught me that fund manager selection on people, just like direct investing on people, could also yield great returns (see HBV's extended return on Billiontoone on a magnitude of +50% as a result of an ownership position in a FoF investment)

The revenue implications of this are tremendous. Applied Compute's founder recently tweeted a cryptic "12.8M annualized." This is not a dig at all at the AC founders who I think are incredibly smart and working on RLaaS in its value-driven primitives, but I'd hazard a guess that much of this is annualized pilot revenue driven by either introductions from multistage investor backers or reputation from being backed by those backers.

In smaller, more intimate conversations with first design customers at hyperscaler logos being kingmade, they are not fundamentally better than any other founder or product. They churn the same, they come across the same worries, they react accordingly to the same customer insights that most other founders (in absentia of a check from Sequoia), would. They might even command a higher premium for their product, or pilots, or conversion KPIs, just by having been kingmade.

We see an earlier prototypical version of this phenomenon with YC. YC companies, joked about for selling to each other, made it obvious that "YC's customer network" became a real value add and justification for dilution. I also wrote about how accelerators subsequently pass this dilution tax along to the seed investors afterwards, reducing the TAM for traditional venture firms by artificially reducing the number of alpha-finding questions the traditional venture firms could have answered about a company.

This phenomenon presumably disappears at IPO. Purchasing decisions at publicly traded companies are largely agnostic of private investors because their majority shareholders are market players who aren't sophisticated enough to form together cohesively and force procurement decisions. It becomes very easy to kingmake in high customer concentration industries like human data/rl env/AI infra companies today because that's how they're structured. A legacy example people often forget is the commercial and cargo aviation industry, where customer concentration endures largely because of government regulation, where flight SaaS products are incredibly easy to kingmake and entrench because of the ability for fewer larger stakeholders to operate/coordinate deals and practices effectively (see Jeppesen).

Although Figma was not king-made in the sense that we see AI players are today, its disparity between private market and public market valuations is direct evidence of this. More academic literature has long espoused IPOs underperform relative to benchmark stocks in the long run, but this suggests a strong disparity between private/public market valuations today, especially made sustainable by the fact that private markets investors made strong returns at all stages of the process.

Kingmaking and the definition of alpha

Roelof Botha recently said that there are "a limited amount of high quality deals" every year such that return free risk is compounding. What he really means is that, if you take beta-seeking VC firms' definition of consensus deals (large TAMs, pedigreed founders, well referenced and customer traction with recognizable logos), those are becoming more easily tracked and fought over. Early opportunities in early stage, when non-consensus, are decidedly "non-high quality."

In times like these, alpha's definition matters more than ever. Non consensus investing is the only way to capture price asymmetries if companies are increasingly priced higher based on their backers, which are increasingly recognized as a primary GTM channel.

The adage I mentioned in the beginning is a view that is dispersed by the typical shortcomings of large and entrenched organizations. Top-line innovation is scarcely maintained consistently at top performance in large organizations, especially as the large organization, once known for being the "cursor of its category" begins seeing people optimizing to get into it as a badge of honor. This is another reason why alpha bleeds from pedigreed hot startups as it seeks similar talent concentrations that are hard to maintain at scale (with the same early stage incentives).

Growth investors literally say they look for hiring and fundraising chops in their CEOs. Inherently, this has to breed a different type of organization at scale.

To play devil's advocate, however, non-consensus investing is getting really hard. Because objectively, there are so many early talent signals, and badges that some would say are "basic measures of competency," that bring early talent to light. Cory Levy visiting Thomas Jefferson High School, for example, is strong empirical evidence that the true "high quality" outlier founders should have been found by a Z Fellow persona type is being looked over by seed investors.

Kingmaking and talent aggregation

On learning about the recent investments I mentioned at the start of this piece, I joked to my growth investor friend that these companies "become more real the more money investors give them."

I took a shower and realized how stupid that statement must sound to some investors; of course companies became more real the more money investors gave them! If we price companies based on the number of unknown questions they have as to whether they "are a good, fundamental company," then this holds as just a restatement.

Perhaps the difference nowadays, is that while investors priced on unknowns before and were relatively hands off, today they can be hands on with value add just through capital deployment signaling elsewhere and connecting portcos in group chats. I honestly don't even think most of it is done actively anymore; the Applied Computes and Mercors of the world will work together by definition.

Purists at multi-stages would probably then argue that the talent density in both companies is why they're working together, not nebulous capital puppeteering. "There aren't that many talents at up and coming companies that can make sense of Mercor's data to build the products and models that Mercor wants." I argue then, how did that perceived "talent density" get there in the first place? But then again, advertising and mindshare from the multistage funds on x would have also probably influenced a procurement decision for AC by Mercor as well, lending more fuel to the argument of accruing private capital advantages.

Kingmaking as a leading indicator

At the end of all of this roundabout analysis, I have to unhappily concede that, unfortunately, king making is real. It pains me as an investor who learned much of their craft and got to see a lot of their deals at boutique firms who are venture purists. It would pain me especially if I still worked at a fund like Hummingbird Ventures, who prides themselves on first principles people selection without any thought as to the accruing advantages of private capital.

This is not to say that traditional venture strategies don't work anymore. Its more of:

- The Bifurcation of Venture (a prime example being Hemant's transformation of GC), many FoF have written much better than me on this

- The Validation of Kingmaking by beta seeking vc firms

- The increasing interface between alpha and beta seeking vc firms, whereas alpha driven firms derive much of their returns from beta seeking markups

- Betting on people is, and will always ever be, the only constant in early stage investing

If you believe this, then the recent migration of the few junior vc talents to founding positions make sense. If familiarity with private capital products in venture markets is increasingly an advantage, than more quests will be made from usurpers and suitors for premature kings' thrones will proliferate. Very interesting as good junior VCs skillsets revolve answering as many questions as possible about a startup in its early stage so as to make outsized alpha seeking decisions, or building network to support that. Those networks, it seems, will have other uses in king-seeking quests. Given this assumption about junior vcs' skillsets, Decagon, Parallel Web Systems, and Cursor have done well to focus on hiring vc talent, even if unintentional.

There's also potentially a longer conversation here to be had on whether this is leading indicator of anti-competitive practices in this industry. Large multi-stage venture investments and backing are starting to have the same effect of large public company announcements of procurements from other large public companies, but lack the transparency in public markets for stakeholders to know what's going on. When AC says Mercor is a customer, do people actually know what the use case was, or if the pilot converted? When 11x claims logos as customers, are they actual ARR or 3 month pilots? When Sequoia backs a company in a space, how do so many others get scared enough to not make their own bets, or to compete themselves in that space?

I'm not sure what fundamental shift has happened to precipitate this behavior, or whether this is the natural result of increasing venture capital market maturation (just like private equity maturation a decade ago), and would welcome further discussion by anyone who'd love to jam more at cr4sean@gmail.com.

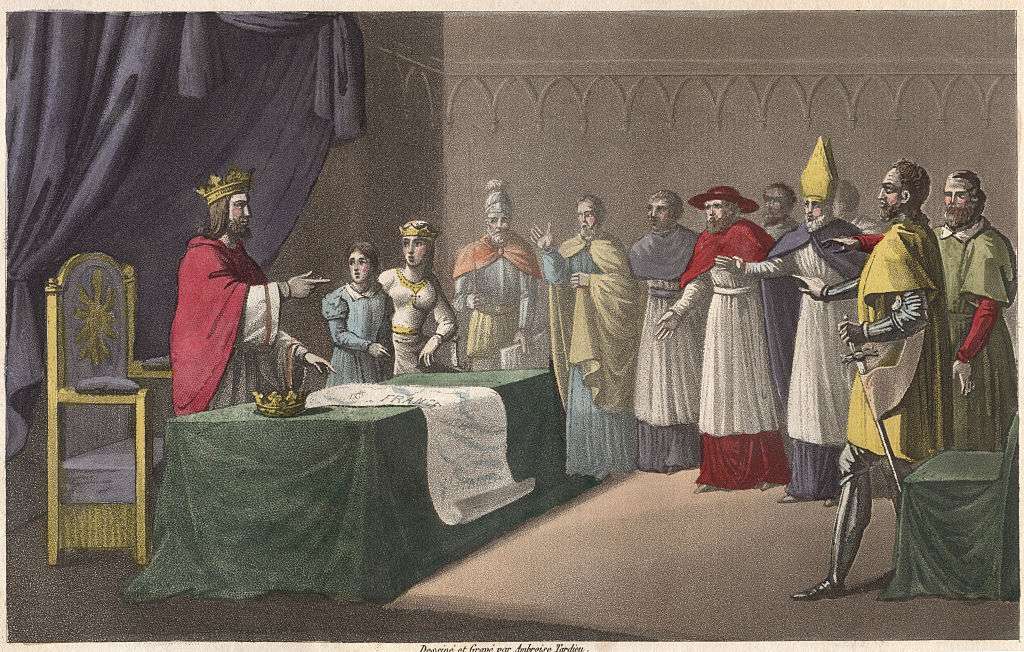

Its 843 CE and the Treaty of Verdun has just been signed. Charlemagne's empire has just been carved up and tiny kingdoms are being assigned to political families - each region crowned its own sovereign - not through superiority, but through inheritance from the right house. Multi-stage funds are today's Carolingian equivalents: dividing markets, assigning territory, and legitimizing leaders whose power is derivative of their capital lineage.

The crowns are being handed out now - but as William the Invader in 1066 proved, history remembers the invaders, not the inheritors.

In the same way, capital may divide today's kingdoms, but the next empire won't be inherited.

It will be taken.

Louis the Pious dividing up his empire between his children (840), which would then divide further into the HRE / Contributor / Getty Images